编者按:《我們難民》(We Refugees)寫於1943年初,正是漢娜·阿倫特抵達美國後不到兩年、納粹對歐洲猶太人滅絕行動最殘酷的時期。她1933年逃離德國,經布拉格、巴黎,1941年5月才輾轉抵達紐約,當時歐陸幾乎全部落入納粹之手,數十萬猶太人正被送往滅絕營。阿倫特自己剛剛拿到美國的「外僑登記證」,尚未入籍,卻已深刻感受到「難民」身份的荒誕與屈辱。

這篇文章最初發表於1943年春季的《The Menorah Journal》(《光明節雜誌》),這是一份紐約的猶太知識分子小型英文季刊,讀者主要是美國化的德裔與東歐裔猶太人。文章以第一人稱複數「我們」寫成,語氣冷靜、諷刺、帶著難以掩飾的憤怒,一出版便在猶太難民社群引起巨大震撼。許多讀者寫信給編輯說「這正是我不敢說出口的話」。因為寫得太直白、太不「感恩」,當時美國主流猶太組織曾私下批評它「給難民抹黑」。然而正是這篇不到三千字的短文,奠定了阿倫特戰後思想的三大核心:無國籍狀態如何剝奪人權、極權如何摧毀私人生活、難民作為現代政治狀況的極端象徵。後來《極權主義的起源》(1951)裡關於「無國籍者」與「難民」的經典分析,都可視為這篇1943年小文的擴展與深化。它也是阿倫特用英文寫作的第一篇重要政治文本,標誌著她從德語知識分子徹底轉向英語世界公共思想家的轉折。

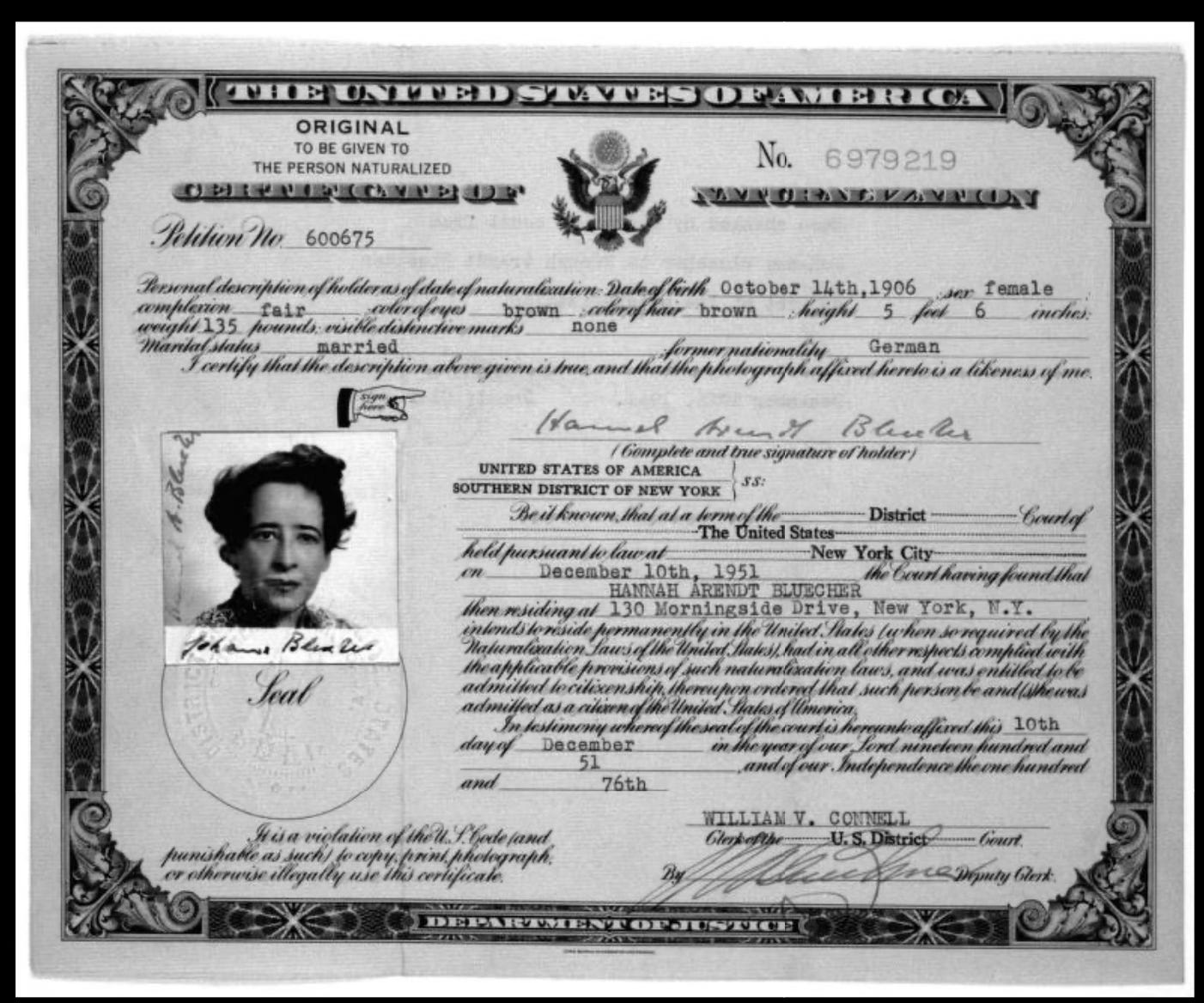

波士頓書評在國會圖書館找到阿倫特漢娜·阿倫特正式成為美國公民的歸化證書(Certificate of Naturalization)。阿倫特1941年5月作為難民逃到美國,足足等了10年零7個月,才在1951年12月10日這一天正式宣誓成為美國公民。這張證書是她人生中最重要的一份文件之一。她後來常說:“我這一生最想做的只有一件事:重新擁有政治身份。”這張紙,終結了她長達18年的無國籍狀態(1933–1951)。在難民危機的今天,波士頓書評重新翻譯阿倫特這篇文章,紀念漢娜·阿倫特(Hannah Arendt)去世五十週年。

我們難民

漢娜·阿倫特(1943)

首先,我們不喜歡被稱為「難民」。我們自己互相稱呼對方為「新來者」或「移民」。我們的報紙是給「德語美國人」看的報紙;據我所知,從來沒有、也從未存在過任何一個由希特勒迫害的人創辦的俱樂部,名字裡寫明其成員是難民。

過去的難民,是因為種族或政治信仰被驅逐的人。新型難民,是因為拒絕成為迫害者而被驅逐的人。這差別絕不只是學術上的。舊式難民在風暴過去後,還有一個國家可以回去。新型難民沒有國家可以回去;他們是歷史上第一批非宗教的殉道者。

我們是第一批非宗教的殉道者。地獄不再是宗教信仰或幻想,而是在塵世真實發生的事。在集中營裡,人們被殺不是因為犯了什麼罪,而是因為他們是猶太人。

我們失去了家園,這意味著日常生活的熟悉感。我們失去了職業,這意味著確信自己對這個世界還有用處的信心。我們失去了語言,這意味著反應的自然、手勢的簡單、情感的真摯表達。我們把親人留在波蘭隔都裡,我們最好的朋友在集中營被殺,這意味著我們私人生活的斷裂。

然而,我們一被救出來——我們當中大多數人都被救過好幾次——就開始新生活,並盡快忘掉之前發生的一切。當然,也有一些不幸的例外,因為各種原因無法遵守這條規則。他們是被稱為「樂觀主義者」的人,相信一切又會好起來,或是「悲觀主義者」,相信一切永遠失去了。這兩種人在社群裡都不太受歡迎。樂觀主義者被認為「太天真」,悲觀主義者「太悲觀」。

然而我們大多數人,都努力適應新國家,盡快忘掉舊國家。我們越沒有自由決定自己是誰、按自己喜歡的方式生活,就越想撐起門面,在驕傲的外殼後面躲藏。我們越不被當人對待,就越努力讓自己看起來像個人。

我們不想當難民;我們想當美國人、法國人、英國人——什麼都好,就是不要當難民。

我們盡快成為公民,對每一張宣告我們是公民的文件都心存感激。我們盡快同化,對每一點被接納的跡象都讓我們感激。我們不要被憐憫;我們要被尊重。我們不想成為問題;我們想成為答案。

然而——我們當中仍有一些人還沒忘記自己是難民。他們知道自己不屬於這個世界,是異鄉人,而且永遠是異鄉人。他們知道自己失去了一切,也沒有什麼可再失去的了。他們知道自己自由了——擺脫一切社會紐帶、一切國族效忠、一切責任。他們是自己民族的先鋒——如果那個民族還存在的話。

我們必須帶著這份認知活下去。我們必須接受自己是第一批非宗教殉道者的事實。我們必須接受自己是歷史上第一批被明白告知「哪裡都不歡迎你們」的人的事實。我們必須接受自己是第一批被自己政府剝奪國籍的人的事實。

然而——我們還活著。我們仍然是人。我們仍然懷抱希望。我們仍然相信,終有一天我們會被接納——不是作為難民,而是作為人。

We Refugees

Hannah Arendt

First published in The Menorah Journal, Vol. 31, No. 1 (Spring 1943), pp. 69–77.

In the first place, we don’t like to be called “refugees.” We ourselves call each other “newcomers” or “immigrants.” Our newspapers are papers for “Americans of German language”; and, as far as I know, there is not and never was any club founded by Hitler-persecuted people whose name indicated that its members were refugees.

A refugee used to be a person driven out on account of race or political creed. The new type of refugee is a person who has been driven out because he refused to be a persecutor. The difference is not merely academic. The old refugees had a country to return to when the storm was over. The new ones have no country to return to; they are the first non-religious martyrs in history.

We are the first non-religious martyrs. Hell is no longer a religious belief or a fantasy, but something real that is happening here on earth. In the concentration camps people were killed not because they had been guilty of anything but because they were Jews. We lost our home, which means the familiarity of daily life. We lost our occupation, which means the confidence that we are of some use in this world. We lost our language, which means the naturalness of reactions, the simplicity of gestures, the unaffected expression of feelings. We left our relatives in the Polish ghettos and our best friends have been killed in concentration camps, and that means the rupture of our private lives.

Nevertheless, as soon as we were saved—and most of us had to be saved several times—we started our new lives and tried to forget as quickly as possible all that had happened before. There are, of course, some unhappy exceptions who, for various reasons, cannot follow this rule. They are the “optimists” who believe that everything will be all right again, or the “pessimists” who believe that everything is lost forever. Both groups are not very popular in the community. The optimists are considered to be “too naïve, the pessimists too pessimistic. The majority of us, however, try to adjust ourselves to the new country and to forget the old one as quickly as possible.

The less we are free to decide who we are or to live as we like, the more we try to put up a front, to hide the world a proud façade. The less we are treated as human beings, the more we try to look like human beings. We don’t want to be refugees; we want to be Americans, Frenchmen, Englishmen—anything but refugees.

We try to become citizens as quickly as possible, and we are grateful for every document that proclaims us citizens. We try to become assimilated as quickly as possible, and we are grateful for every sign that we are accepted. We don’t want to be pitied; we want to be respected. We don’t want to be a problem; we want to be a solution.

And yet—there is a few among us who have not yet forgotten that we are refugees. They know that they are not at home in this world, that they are strangers and that they will remain strangers. They know that they have lost everything and that they have nothing to lose. They know that they are free—free from all social ties, free from all national allegiances, free from all responsibilities. They are the vanguard of their people—if their people still exist.

We have to live with this knowledge. We have to live with the fact that we are the first non-religious martyrs. We have to live with the fact that we are the first people in history who have been told that they are not wanted anywhere. We have to live with the fact that we are the first people who have been made stateless by their own governments.

And yet—we are still alive. We are still human beings. We still hope. And we still believe that one day we shall be accepted—not as refugees, but as human beings.

由于美国政治环境的变化,《中国民主季刊》资金来源变得不稳定。如果您认同季刊的价值,请打赏、支持。当然,您可以点击“稍后再说”,而直接阅读或下载。谢谢您,亲爱的读者。